找到

227

篇与

科普知识

相关的结果

-

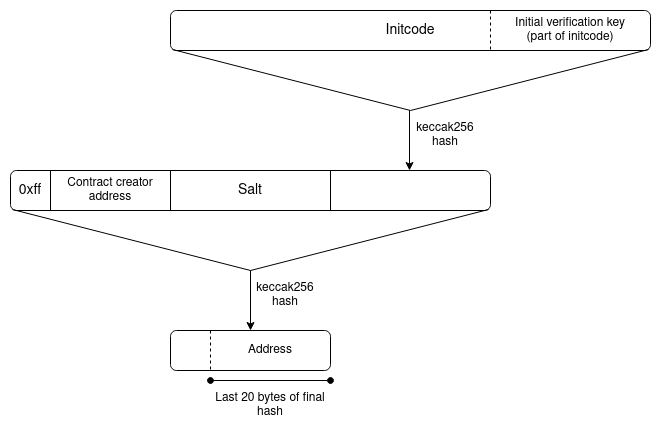

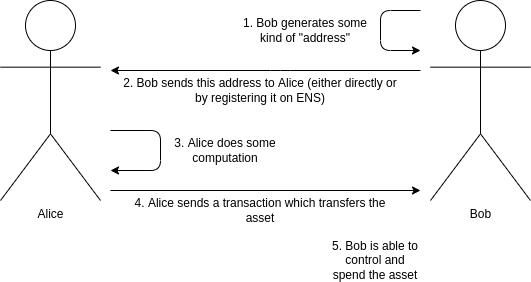

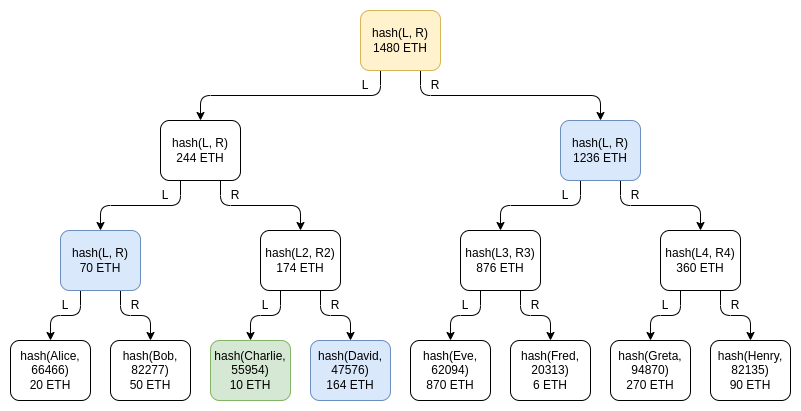

Deeper dive on cross-L2 reading for wallets and other use cases Deeper dive on cross-L2 reading for wallets and other use cases2023 Jun 20 See all posts Deeper dive on cross-L2 reading for wallets and other use cases Special thanks to Yoav Weiss, Dan Finlay, Martin Koppelmann, and the Arbitrum, Optimism, Polygon, Scroll and SoulWallet teams for feedback and review.In this post on the Three Transitions, I outlined some key reasons why it's valuable to start thinking explicitly about L1 + cross-L2 support, wallet security, and privacy as necessary basic features of the ecosystem stack, rather than building each of these things as addons that can be designed separately by individual wallets.This post will focus more directly on the technical aspects of one specific sub-problem: how to make it easier to read L1 from L2, L2 from L1, or an L2 from another L2. Solving this problem is crucial for implementing an asset / keystore separation architecture, but it also has valuable use cases in other areas, most notably optimizing reliable cross-L2 calls, including use cases like moving assets between L1 and L2s.Recommended pre-readsPost on the Three Transitions Ideas from the Safe team on holding assets across multiple chains Why we need wide adoption of social recovery wallets ZK-SNARKs, and some privacy applications Dankrad on KZG commitments Verkle trees Table of contentsWhat is the goal? What does a cross-chain proof look like? What kinds of proof schemes can we use? Merkle proofs ZK SNARKs Special purpose KZG proofs Verkle tree proofs Aggregation Direct state reading How does L2 learn the recent Ethereum state root? Wallets on chains that are not L2s Preserving privacy Summary What is the goal?Once L2s become more mainstream, users will have assets across multiple L2s, and possibly L1 as well. Once smart contract wallets (multisig, social recovery or otherwise) become mainstream, the keys needed to access some account are going to change over time, and old keys would need to no longer be valid. Once both of these things happen, a user will need to have a way to change the keys that have authority to access many accounts which live in many different places, without making an extremely high number of transactions.Particularly, we need a way to handle counterfactual addresses: addresses that have not yet been "registered" in any way on-chain, but which nevertheless need to receive and securely hold funds. We all depend on counterfactual addresses: when you use Ethereum for the first time, you are able to generate an ETH address that someone can use to pay you, without "registering" the address on-chain (which would require paying txfees, and hence already holding some ETH).With EOAs, all addresses start off as counterfactual addresses. With smart contract wallets, counterfactual addresses are still possible, largely thanks to CREATE2, which allows you to have an ETH address that can only be filled by a smart contract that has code matching a particular hash. EIP-1014 (CREATE2) address calculation algorithm. However, smart contract wallets introduce a new challenge: the possibility of access keys changing. The address, which is a hash of the initcode, can only contain the wallet's initial verification key. The current verification key would be stored in the wallet's storage, but that storage record does not magically propagate to other L2s.If a user has many addresses on many L2s, including addresses that (because they are counterfactual) the L2 that they are on does not know about, then it seems like there is only one way to allow users to change their keys: asset / keystore separation architecture. Each user has (i) a "keystore contract" (on L1 or on one particular L2), which stores the verification key for all wallets along with the rules for changing the key, and (ii) "wallet contracts" on L1 and many L2s, which read cross-chain to get the verification key. There are two ways to implement this:Light version (check only to update keys): each wallet stores the verification key locally, and contains a function which can be called to check a cross-chain proof of the keystore's current state, and update its locally stored verification key to match. When a wallet is used for the first time on a particular L2, calling that function to obtain the current verification key from the keystore is mandatory. Upside: uses cross-chain proofs sparingly, so it's okay if cross-chain proofs are expensive. All funds are only spendable with the current keys, so it's still secure. Downside: To change the verification key, you have to make an on-chain key change in both the keystore and in every wallet that is already initialized (though not counterfactual ones). This could cost a lot of gas. Heavy version (check for every tx): a cross-chain proof showing the key currently in the keystore is necessary for each transaction. Upside: less systemic complexity, and keystore updating is cheap. Downside: expensive per-tx, so requires much more engineering to make cross-chain proofs acceptably cheap. Also not easily compatible with ERC-4337, which currently does not support cross-contract reading of mutable objects during validation. What does a cross-chain proof look like?To show the full complexity, we'll explore the most difficult case: where the keystore is on one L2, and the wallet is on a different L2. If either the keystore or the wallet is on L1, then only half of this design is needed. Let's assume that the keystore is on Linea, and the wallet is on Kakarot. A full proof of the keys to the wallet consists of:A proof proving the current Linea state root, given the current Ethereum state root that Kakarot knows about A proof proving the current keys in the keystore, given the current Linea state root There are two primary tricky implementation questions here:What kind of proof do we use? (Is it Merkle proofs? something else?) How does the L2 learn the recent L1 (Ethereum) state root (or, as we shall see, potentially the full L1 state) in the first place? And alternatively, how does the L1 learn the L2 state root? In both cases, how long are the delays between something happening on one side, and that thing being provable to the other side? What kinds of proof schemes can we use?There are five major options:Merkle proofs General-purpose ZK-SNARKs Special-purpose proofs (eg. with KZG) Verkle proofs, which are somewhere between KZG and ZK-SNARKs on both infrastructure workload and cost. No proofs and rely on direct state reading In terms of infrastructure work required and cost for users, I rank them roughly as follows: "Aggregation" refers to the idea of aggregating all the proofs supplied by users within each block into a big meta-proof that combines all of them. This is possible for SNARKs, and for KZG, but not for Merkle branches (you can combine Merkle branches a little bit, but it only saves you log(txs per block) / log(total number of keystores), perhaps 15-30% in practice, so it's probably not worth the cost).Aggregation only becomes worth it once the scheme has a substantial number of users, so realistically it's okay for a version-1 implementation to leave aggregation out, and implement that for version 2.How would Merkle proofs work?This one is simple: follow the diagram in the previous section directly. More precisely, each "proof" (assuming the max-difficulty case of proving one L2 into another L2) would contain:A Merkle branch proving the state-root of the keystore-holding L2, given the most recent state root of Ethereum that the L2 knows about. The keystore-holding L2's state root is stored at a known storage slot of a known address (the contract on L1 representing the L2), and so the path through the tree could be hardcoded. A Merkle branch proving the current verification keys, given the state-root of the keystore-holding L2. Here once again, the verification key is stored at a known storage slot of a known address, so the path can be hardcoded. Unfortunately, Ethereum state proofs are complicated, but there exist libraries for verifying them, and if you use these libraries, this mechanism is not too complicated to implement.The larger problem is cost. Merkle proofs are long, and Patricia trees are unfortunately ~3.9x longer than necessary (precisely: an ideal Merkle proof into a tree holding N objects is 32 * log2(N) bytes long, and because Ethereum's Patricia trees have 16 leaves per child, proofs for those trees are 32 * 15 * log16(N) ~= 125 * log2(N) bytes long). In a state with roughly 250 million (~2²⁸) accounts, this makes each proof 125 * 28 = 3500 bytes, or about 56,000 gas, plus extra costs for decoding and verifying hashes.Two proofs together would end up costing around 100,000 to 150,000 gas (not including signature verification if this is used per-transaction) - significantly more than the current base 21,000 gas per transaction. But the disparity gets worse if the proof is being verified on L2. Computation inside an L2 is cheap, because computation is done off-chain and in an ecosystem with much fewer nodes than L1. Data, on the other hand, has to be posted to L1. Hence, the comparison is not 21000 gas vs 150,000 gas; it's 21,000 L2 gas vs 100,000 L1 gas.We can calculate what this means by looking at comparisons between L1 gas costs and L2 gas costs: L1 is currently about 15-25x more expensive than L2 for simple sends, and 20-50x more expensive for token swaps. Simple sends are relatively data-heavy, but swaps are much more computationally heavy. Hence, swaps are a better benchmark to approximate cost of L1 computation vs L2 computation. Taking all this into account, if we assume a 30x cost ratio between L1 computation cost and L2 computation cost, this seems to imply that putting a Merkle proof on L2 will cost the equivalent of perhaps fifty regular transactions.Of course, using a binary Merkle tree can cut costs by ~4x, but even still, the cost is in most cases going to be too high - and if we're willing to make the sacrifice of no longer being compatible with Ethereum's current hexary state tree, we might as well seek even better options.How would ZK-SNARK proofs work?Conceptually, the use of ZK-SNARKs is also easy to understand: you simply replace the Merkle proofs in the diagram above with a ZK-SNARK proving that those Merkle proofs exist. A ZK-SNARK costs ~400,000 gas of computation, and about 400 bytes (compare: 21,000 gas and 100 bytes for a basic transaction, in the future reducible to ~25 bytes with compression). Hence, from a computational perspective, a ZK-SNARK costs 19x the cost of a basic transaction today, and from a data perspective, a ZK-SNARK costs 4x as much as a basic transaction today, and 16x what a basic transaction may cost in the future.These numbers are a massive improvement over Merkle proofs, but they are still quite expensive. There are two ways to improve on this: (i) special-purpose KZG proofs, or (ii) aggregation, similar to ERC-4337 aggregation but using more fancy math. We can look into both.How would special-purpose KZG proofs work?Warning, this section is much more mathy than other sections. This is because we're going beyond general-purpose tools and building something special-purpose to be cheaper, so we have to go "under the hood" a lot more. If you don't like deep math, skip straight to the next section.First, a recap of how KZG commitments work:We can represent a set of data [D_1 ... D_n] with a KZG proof of a polynomial derived from the data: specifically, the polynomial P where P(w) = D_1, P(w²) = D_2 ... P(wⁿ) = D_n. w here is a "root of unity", a value where wᴺ = 1 for some evaluation domain size N (this is all done in a finite field). To "commit" to P, we create an elliptic curve point com(P) = P₀ * G + P₁ * S₁ + ... + Pₖ * Sₖ. Here: G is the generator point of the curve Pᵢ is the i'th-degree coefficient of the polynomial P Sᵢ is the i'th point in the trusted setup To prove P(z) = a, we create a quotient polynomial Q = (P - a) / (X - z), and create a commitment com(Q) to it. It is only possible to create such a polynomial if P(z) actually equals a. To verify a proof, we check the equation Q * (X - z) = P - a by doing an elliptic curve check on the proof com(Q) and the polynomial commitment com(P): we check e(com(Q), com(X - z)) ?= e(com(P) - com(a), com(1)) Some key properties that are important to understand are:A proof is just the com(Q) value, which is 48 bytes com(P₁) + com(P₂) = com(P₁ + P₂) This also means that you can "edit" a value into an existing a commitment. Suppose that we know that D_i is currently a, we want to set it to b, and the existing commitment to D is com(P). A commitment to "P, but with P(wⁱ) = b, and no other evaluations changed", then we set com(new_P) = com(P) + (b-a) * com(Lᵢ), where Lᵢ is a the "Lagrange polynomial" that equals 1 at wⁱ and 0 at other wʲ points. To perform these updates efficiently, all N commitments to Lagrange polynomials (com(Lᵢ)) can be pre-calculated and stored by each client. Inside a contract on-chain it may be too much to store all N commitments, so instead you could make a KZG commitment to the set of com(L_i) (or hash(com(L_i)) values, so whenever someone needs to update the tree on-chain they can simply provide the appropriate com(L_i) with a proof of its correctness. Hence, we have a structure where we can just keep adding values to the end of an ever-growing list, though with a certain size limit (realistically, hundreds of millions could be viable). We then use that as our data structure to manage (i) a commitment to the list of keys on each L2, stored on that L2 and mirrored to L1, and (ii) a commitment to the list of L2 key-commitments, stored on the Ethereum L1 and mirrored to each L2.Keeping the commitments updated could either become part of core L2 logic, or it could be implemented without L2 core-protocol changes through deposit and withdraw bridges. A full proof would thus require:The latest com(key list) on the keystore-holding L2 (48 bytes) KZG proof of com(key list) being a value inside com(mirror_list), the commitment to the list of all key list comitments (48 bytes) KZG proof of your key in com(key list) (48 bytes, plus 4 bytes for the index) It's actually possible to merge the two KZG proofs into one, so we get a total size of only 100 bytes.Note one subtlety: because the key list is a list, and not a key/value map like the state is, the key list will have to assign positions sequentially. The key commitment contract would contain its own internal registry mapping each keystore to an ID, and for each key it would store hash(key, address of the keystore) instead of just key, to unambiguously communicate to other L2s which keystore a particular entry is talking about.The upside of this technique is that it performs very well on L2. The data is 100 bytes, ~4x shorter than a ZK-SNARK and waaaay shorter than a Merkle proof. The computation cost is largely one size-2 pairing check, or about 119,000 gas. On L1, data is less important than computation, and so unfortunately KZG is somewhat more expensive than Merkle proofs.How would Verkle trees work?Verkle trees essentially involve stacking KZG commitments (or IPA commitments, which can be more efficient and use simpler cryptography) on top of each other: to store 2⁴⁸ values, you can make a KZG commitment to a list of 2²⁴ values, each of which itself is a KZG commitment to 2²⁴ values. Verkle trees are being strongly considered for the Ethereum state tree, because Verkle trees can be used to hold key-value maps and not just lists (basically, you can make a size-2²⁵⁶ tree but start it empty, only filling in specific parts of the tree once you actually need to fill them). What a Verkle tree looks like. In practice, you might give each node a width of 256 == 2⁸ for IPA-based trees, or 2²⁴ for KZG-based trees. Proofs in Verkle trees are somewhat longer than KZG; they might be a few hundred bytes long. They are also difficult to verify, especially if you try to aggregate many proofs into one.Realistically, Verkle trees should be considered to be like Merkle trees, but more viable without SNARKing (because of the lower data costs), and cheaper with SNARKing (because of lower prover costs).The largest advantage of Verkle trees is the possibility of harmonizing data structures: Verkle proofs could be used directly over L1 or L2 state, without overlay structures, and using the exact same mechanism for L1 and L2. Once quantum computers become an issue, or once proving Merkle branches becomes efficient enough, Verkle trees could be replaced in-place with a binary hash tree with a suitable SNARK-friendly hash function.AggregationIf N users make N transactions (or more realistically, N ERC-4337 UserOperations) that need to prove N cross-chain claims, we can save a lot of gas by aggregating those proofs: the builder that would be combining those transactions into a block or bundle that goes into a block can create a single proof that proves all of those claims simultaneously.This could mean:A ZK-SNARK proof of N Merkle branches A KZG multi-proof A Verkle multi-proof (or a ZK-SNARK of a multi-proof) In all three cases, the proofs would only cost a few hundred thousand gas each. The builder would need to make one of these on each L2 for the users in that L2; hence, for this to be useful to build, the scheme as a whole needs to have enough usage that there are very often at least a few transactions within the same block on multiple major L2s.If ZK-SNARKs are used, the main marginal cost is simply "business logic" of passing numbers around between contracts, so perhaps a few thousand L2 gas per user. If KZG multi-proofs are used, the prover would need to add 48 gas for each keystore-holding L2 that is used within that block, so the marginal cost of the scheme per user would add another ~800 L1 gas per L2 (not per user) on top. But these costs are much lower than the costs of not aggregating, which inevitably involve over 10,000 L1 gas and hundreds of thousands of L2 gas per user. For Verkle trees, you can either use Verkle multi-proofs directly, adding around 100-200 bytes per user, or you can make a ZK-SNARK of a Verkle multi-proof, which has similar costs to ZK-SNARKs of Merkle branches but is significantly cheaper to prove.From an implementation perspective, it's probably best to have bundlers aggregate cross-chain proofs through the ERC-4337 account abstraction standard. ERC-4337 already has a mechanism for builders to aggregate parts of UserOperations in custom ways. There is even an implementation of this for BLS signature aggregation, which could reduce gas costs on L2 by 1.5x to 3x depending on what other forms of compression are included. Diagram from a BLS wallet implementation post showing the workflow of BLS aggregate signatures within an earlier version of ERC-4337. The workflow of aggregating cross-chain proofs will likely look very similar.Direct state readingA final possibility, and one only usable for L2 reading L1 (and not L1 reading L2), is to modify L2s to let them make static calls to contracts on L1 directly.This could be done with an opcode or a precompile, which allows calls into L1 where you provide the destination address, gas and calldata, and it returns the output, though because these calls are static-calls they cannot actually change any L1 state. L2s have to be aware of L1 already to process deposits, so there is nothing fundamental stopping such a thing from being implemented; it is mainly a technical implementation challenge (see: this RFP from Optimism to support static calls into L1).Notice that if the keystore is on L1, and L2s integrate L1 static-call functionality, then no proofs are required at all! However, if L2s don't integrate L1 static-calls, or if the keystore is on L2 (which it may eventually have to be, once L1 gets too expensive for users to use even a little bit), then proofs will be required.How does L2 learn the recent Ethereum state root?All of the schemes above require the L2 to access either the recent L1 state root, or the entire recent L1 state. Fortunately, all L2s have some functionality to access the recent L1 state already. This is because they need such a functionality to process messages coming in from L1 to the L2, most notably deposits.And indeed, if an L2 has a deposit feature, then you can use that L2 as-is to move L1 state roots into a contract on the L2: simply have a contract on L1 call the BLOCKHASH opcode, and pass it to L2 as a deposit message. The full block header can be received, and its state root extracted, on the L2 side. However, it would be much better for every L2 to have an explicit way to access either the full recent L1 state, or recent L1 state roots, directly.The main challenge with optimizing how L2s receive recent L1 state roots is simultaneously achieving safety and low latency:If L2s implement "direct reading of L1" functionality in a lazy way, only reading finalized L1 state roots, then the delay will normally be 15 minutes, but in the extreme case of inactivity leaks (which you have to tolerate), the delay could be several weeks. L2s absolutely can be designed to read much more recent L1 state roots, but because L1 can revert (even with single slot finality, reverts can happen during inactivity leaks), L2 would need to be able to revert as well. This is technically challenging from a software engineering perspective, but at least Optimism already has this capability. If you use the deposit bridge to bring L1 state roots into L2, then simple economic viability might require a long time between deposit updates: if the full cost of a deposit is 100,000 gas, and we assume ETH is at $1800, and fees are at 200 gwei, and L1 roots are brought into L2 once per day, that would be a cost of $36 per L2 per day, or $13148 per L2 per year to maintain the system. With a delay of one hour, that goes up to $315,569 per L2 per year. In the best case, a constant trickle of impatient wealthy users covers the updating fees and keep the system up to date for everyone else. In the worst case, some altruistic actor would have to pay for it themselves. "Oracles" (at least, the kind of tech that some defi people call "oracles") are not an acceptable solution here: wallet key management is a very security-critical low-level functionality, and so it should depend on at most a few pieces of very simple, cryptographically trustless low-level infrastructure. Additionally, in the opposite direction (L1s reading L2):On optimistic rollups, state roots take one week to reach L1 because of the fraud proof delay. On ZK rollups it takes a few hours for now because of a combination of proving times and economic limits, though future technology will reduce this. Pre-confirmations (from sequencers, attesters, etc) are not an acceptable solution for L1 reading L2. Wallet management is a very security-critical low-level functionality, and so the level of security of the L2 -> L1 communication must be absolute: it should not even be possible to push a false L1 state root by taking over the L2 validator set. The only state roots the L1 should trust are state roots that have been accepted as final by the L2's state-root-holding contract on L1. Some of these speeds for trustless cross-chain operations are unacceptably slow for many defi use cases; for those cases, you do need faster bridges with more imperfect security models. For the use case of updating wallet keys, however, longer delays are more acceptable: you're not delaying transactions by hours, you're delaying key changes. You'll just have to keep the old keys around longer. If you're changing keys because keys are stolen, then you do have a significant period of vulnerability, but this can be mitigated, eg. by wallets having a freeze function.Ultimately, the best latency-minimizing solution is for L2s to implement direct reading of L1 state roots in an optimal way, where each L2 block (or the state root computation log) contains a pointer to the most recent L1 block, so if L1 reverts, L2 can revert as well. Keystore contracts should be placed either on mainnet, or on L2s that are ZK-rollups and so can quickly commit to L1. Blocks of the L2 chain can have dependencies on not just previous L2 blocks, but also on an L1 block. If L1 reverts past such a link, the L2 reverts too. It's worth noting that this is also how an earlier (pre-Dank) version of sharding was envisioned to work; see here for code. How much connection to Ethereum does another chain need to hold wallets whose keystores are rooted on Ethereum or an L2?Surprisingly, not that much. It actually does not even need to be a rollup: if it's an L3, or a validium, then it's okay to hold wallets there, as long as you hold keystores either on L1 or on a ZK rollup. The thing that you do need is for the chain to have direct access to Ethereum state roots, and a technical and social commitment to be willing to reorg if Ethereum reorgs, and hard fork if Ethereum hard forks.One interesting research problem is identifying to what extent it is possible for a chain to have this form of connection to multiple other chains (eg. Ethereum and Zcash). Doing it naively is possible: your chain could agree to reorg if Ethereum or Zcash reorg (and hard fork if Ethereum or Zcash hard fork), but then your node operators and your community more generally have double the technical and political dependencies. Hence such a technique could be used to connect to a few other chains, but at increasing cost. Schemes based on ZK bridges have attractive technical properties, but they have the key weakness that they are not robust to 51% attacks or hard forks. There may be more clever solutions.Preserving privacyIdeally, we also want to preserve privacy. If you have many wallets that are managed by the same keystore, then we want to make sure:It's not publicly known that those wallets are all connected to each other. Social recovery guardians don't learn what the addresses are that they are guarding. This creates a few issues:We cannot use Merkle proofs directly, because they do not preserve privacy. If we use KZG or SNARKs, then the proof needs to provide a blinded version of the verification key, without revealing the location of the verification key. If we use aggregation, then the aggregator should not learn the location in plaintext; rather, the aggregator should receive blinded proofs, and have a way to aggregate those. We can't use the "light version" (use cross-chain proofs only to update keys), because it creates a privacy leak: if many wallets get updated at the same time due to an update procedure, the timing leaks the information that those wallets are likely related. So we have to use the "heavy version" (cross-chain proofs for each transaction). With SNARKs, the solutions are conceptually easy: proofs are information-hiding by default, and the aggregator needs to produce a recursive SNARK to prove the SNARKs. The main challenge of this approach today is that aggregation requires the aggregator to create a recursive SNARK, which is currently quite slow.With KZG, we can use this work on non-index-revealing KZG proofs (see also: a more formalized version of that work in the Caulk paper) as a starting point. Aggregation of blinded proofs, however, is an open problem that requires more attention.Directly reading L1 from inside L2, unfortunately, does not preserve privacy, though implementing direct-reading functionality is still very useful, both to minimize latency and because of its utility for other applications.SummaryTo have cross-chain social recovery wallets, the most realistic workflow is a wallet that maintains a keystore in one location, and wallets in many locations, where wallet reads the keystore either (i) to update their local view of the verification key, or (ii) during the process of verifying each transaction. A key ingredient of making this possible is cross-chain proofs. We need to optimize these proofs hard. Either ZK-SNARKs, waiting for Verkle proofs, or a custom-built KZG solution, seem like the best options. In the longer term, aggregation protocols where bundlers generate aggregate proofs as part of creating a bundle of all the UserOperations that have been submitted by users will be necessary to minimize costs. This should probably be integrated into the ERC-4337 ecosystem, though changes to ERC-4337 will likely be required. L2s should be optimized to minimize the latency of reading L1 state (or at least the state root) from inside the L2. L2s directly reading L1 state is ideal and can save on proof space. Wallets can be not just on L2s; you can also put wallets on systems with lower levels of connection to Ethereum (L3s, or even separate chains that only agree to include Ethereum state roots and reorg or hard fork when Ethereum reorgs or hardforks). However, keystores should be either on L1 or on high-security ZK-rollup L2 . Being on L1 saves a lot of complexity, though in the long run even that may be too expensive, hence the need for keystores on L2. Preserving privacy will require additional work and make some options more difficult. However, we should probably move toward privacy-preserving solutions anyway, and at the least make sure that anything we propose is forward-compatible with preserving privacy.

Deeper dive on cross-L2 reading for wallets and other use cases Deeper dive on cross-L2 reading for wallets and other use cases2023 Jun 20 See all posts Deeper dive on cross-L2 reading for wallets and other use cases Special thanks to Yoav Weiss, Dan Finlay, Martin Koppelmann, and the Arbitrum, Optimism, Polygon, Scroll and SoulWallet teams for feedback and review.In this post on the Three Transitions, I outlined some key reasons why it's valuable to start thinking explicitly about L1 + cross-L2 support, wallet security, and privacy as necessary basic features of the ecosystem stack, rather than building each of these things as addons that can be designed separately by individual wallets.This post will focus more directly on the technical aspects of one specific sub-problem: how to make it easier to read L1 from L2, L2 from L1, or an L2 from another L2. Solving this problem is crucial for implementing an asset / keystore separation architecture, but it also has valuable use cases in other areas, most notably optimizing reliable cross-L2 calls, including use cases like moving assets between L1 and L2s.Recommended pre-readsPost on the Three Transitions Ideas from the Safe team on holding assets across multiple chains Why we need wide adoption of social recovery wallets ZK-SNARKs, and some privacy applications Dankrad on KZG commitments Verkle trees Table of contentsWhat is the goal? What does a cross-chain proof look like? What kinds of proof schemes can we use? Merkle proofs ZK SNARKs Special purpose KZG proofs Verkle tree proofs Aggregation Direct state reading How does L2 learn the recent Ethereum state root? Wallets on chains that are not L2s Preserving privacy Summary What is the goal?Once L2s become more mainstream, users will have assets across multiple L2s, and possibly L1 as well. Once smart contract wallets (multisig, social recovery or otherwise) become mainstream, the keys needed to access some account are going to change over time, and old keys would need to no longer be valid. Once both of these things happen, a user will need to have a way to change the keys that have authority to access many accounts which live in many different places, without making an extremely high number of transactions.Particularly, we need a way to handle counterfactual addresses: addresses that have not yet been "registered" in any way on-chain, but which nevertheless need to receive and securely hold funds. We all depend on counterfactual addresses: when you use Ethereum for the first time, you are able to generate an ETH address that someone can use to pay you, without "registering" the address on-chain (which would require paying txfees, and hence already holding some ETH).With EOAs, all addresses start off as counterfactual addresses. With smart contract wallets, counterfactual addresses are still possible, largely thanks to CREATE2, which allows you to have an ETH address that can only be filled by a smart contract that has code matching a particular hash. EIP-1014 (CREATE2) address calculation algorithm. However, smart contract wallets introduce a new challenge: the possibility of access keys changing. The address, which is a hash of the initcode, can only contain the wallet's initial verification key. The current verification key would be stored in the wallet's storage, but that storage record does not magically propagate to other L2s.If a user has many addresses on many L2s, including addresses that (because they are counterfactual) the L2 that they are on does not know about, then it seems like there is only one way to allow users to change their keys: asset / keystore separation architecture. Each user has (i) a "keystore contract" (on L1 or on one particular L2), which stores the verification key for all wallets along with the rules for changing the key, and (ii) "wallet contracts" on L1 and many L2s, which read cross-chain to get the verification key. There are two ways to implement this:Light version (check only to update keys): each wallet stores the verification key locally, and contains a function which can be called to check a cross-chain proof of the keystore's current state, and update its locally stored verification key to match. When a wallet is used for the first time on a particular L2, calling that function to obtain the current verification key from the keystore is mandatory. Upside: uses cross-chain proofs sparingly, so it's okay if cross-chain proofs are expensive. All funds are only spendable with the current keys, so it's still secure. Downside: To change the verification key, you have to make an on-chain key change in both the keystore and in every wallet that is already initialized (though not counterfactual ones). This could cost a lot of gas. Heavy version (check for every tx): a cross-chain proof showing the key currently in the keystore is necessary for each transaction. Upside: less systemic complexity, and keystore updating is cheap. Downside: expensive per-tx, so requires much more engineering to make cross-chain proofs acceptably cheap. Also not easily compatible with ERC-4337, which currently does not support cross-contract reading of mutable objects during validation. What does a cross-chain proof look like?To show the full complexity, we'll explore the most difficult case: where the keystore is on one L2, and the wallet is on a different L2. If either the keystore or the wallet is on L1, then only half of this design is needed. Let's assume that the keystore is on Linea, and the wallet is on Kakarot. A full proof of the keys to the wallet consists of:A proof proving the current Linea state root, given the current Ethereum state root that Kakarot knows about A proof proving the current keys in the keystore, given the current Linea state root There are two primary tricky implementation questions here:What kind of proof do we use? (Is it Merkle proofs? something else?) How does the L2 learn the recent L1 (Ethereum) state root (or, as we shall see, potentially the full L1 state) in the first place? And alternatively, how does the L1 learn the L2 state root? In both cases, how long are the delays between something happening on one side, and that thing being provable to the other side? What kinds of proof schemes can we use?There are five major options:Merkle proofs General-purpose ZK-SNARKs Special-purpose proofs (eg. with KZG) Verkle proofs, which are somewhere between KZG and ZK-SNARKs on both infrastructure workload and cost. No proofs and rely on direct state reading In terms of infrastructure work required and cost for users, I rank them roughly as follows: "Aggregation" refers to the idea of aggregating all the proofs supplied by users within each block into a big meta-proof that combines all of them. This is possible for SNARKs, and for KZG, but not for Merkle branches (you can combine Merkle branches a little bit, but it only saves you log(txs per block) / log(total number of keystores), perhaps 15-30% in practice, so it's probably not worth the cost).Aggregation only becomes worth it once the scheme has a substantial number of users, so realistically it's okay for a version-1 implementation to leave aggregation out, and implement that for version 2.How would Merkle proofs work?This one is simple: follow the diagram in the previous section directly. More precisely, each "proof" (assuming the max-difficulty case of proving one L2 into another L2) would contain:A Merkle branch proving the state-root of the keystore-holding L2, given the most recent state root of Ethereum that the L2 knows about. The keystore-holding L2's state root is stored at a known storage slot of a known address (the contract on L1 representing the L2), and so the path through the tree could be hardcoded. A Merkle branch proving the current verification keys, given the state-root of the keystore-holding L2. Here once again, the verification key is stored at a known storage slot of a known address, so the path can be hardcoded. Unfortunately, Ethereum state proofs are complicated, but there exist libraries for verifying them, and if you use these libraries, this mechanism is not too complicated to implement.The larger problem is cost. Merkle proofs are long, and Patricia trees are unfortunately ~3.9x longer than necessary (precisely: an ideal Merkle proof into a tree holding N objects is 32 * log2(N) bytes long, and because Ethereum's Patricia trees have 16 leaves per child, proofs for those trees are 32 * 15 * log16(N) ~= 125 * log2(N) bytes long). In a state with roughly 250 million (~2²⁸) accounts, this makes each proof 125 * 28 = 3500 bytes, or about 56,000 gas, plus extra costs for decoding and verifying hashes.Two proofs together would end up costing around 100,000 to 150,000 gas (not including signature verification if this is used per-transaction) - significantly more than the current base 21,000 gas per transaction. But the disparity gets worse if the proof is being verified on L2. Computation inside an L2 is cheap, because computation is done off-chain and in an ecosystem with much fewer nodes than L1. Data, on the other hand, has to be posted to L1. Hence, the comparison is not 21000 gas vs 150,000 gas; it's 21,000 L2 gas vs 100,000 L1 gas.We can calculate what this means by looking at comparisons between L1 gas costs and L2 gas costs: L1 is currently about 15-25x more expensive than L2 for simple sends, and 20-50x more expensive for token swaps. Simple sends are relatively data-heavy, but swaps are much more computationally heavy. Hence, swaps are a better benchmark to approximate cost of L1 computation vs L2 computation. Taking all this into account, if we assume a 30x cost ratio between L1 computation cost and L2 computation cost, this seems to imply that putting a Merkle proof on L2 will cost the equivalent of perhaps fifty regular transactions.Of course, using a binary Merkle tree can cut costs by ~4x, but even still, the cost is in most cases going to be too high - and if we're willing to make the sacrifice of no longer being compatible with Ethereum's current hexary state tree, we might as well seek even better options.How would ZK-SNARK proofs work?Conceptually, the use of ZK-SNARKs is also easy to understand: you simply replace the Merkle proofs in the diagram above with a ZK-SNARK proving that those Merkle proofs exist. A ZK-SNARK costs ~400,000 gas of computation, and about 400 bytes (compare: 21,000 gas and 100 bytes for a basic transaction, in the future reducible to ~25 bytes with compression). Hence, from a computational perspective, a ZK-SNARK costs 19x the cost of a basic transaction today, and from a data perspective, a ZK-SNARK costs 4x as much as a basic transaction today, and 16x what a basic transaction may cost in the future.These numbers are a massive improvement over Merkle proofs, but they are still quite expensive. There are two ways to improve on this: (i) special-purpose KZG proofs, or (ii) aggregation, similar to ERC-4337 aggregation but using more fancy math. We can look into both.How would special-purpose KZG proofs work?Warning, this section is much more mathy than other sections. This is because we're going beyond general-purpose tools and building something special-purpose to be cheaper, so we have to go "under the hood" a lot more. If you don't like deep math, skip straight to the next section.First, a recap of how KZG commitments work:We can represent a set of data [D_1 ... D_n] with a KZG proof of a polynomial derived from the data: specifically, the polynomial P where P(w) = D_1, P(w²) = D_2 ... P(wⁿ) = D_n. w here is a "root of unity", a value where wᴺ = 1 for some evaluation domain size N (this is all done in a finite field). To "commit" to P, we create an elliptic curve point com(P) = P₀ * G + P₁ * S₁ + ... + Pₖ * Sₖ. Here: G is the generator point of the curve Pᵢ is the i'th-degree coefficient of the polynomial P Sᵢ is the i'th point in the trusted setup To prove P(z) = a, we create a quotient polynomial Q = (P - a) / (X - z), and create a commitment com(Q) to it. It is only possible to create such a polynomial if P(z) actually equals a. To verify a proof, we check the equation Q * (X - z) = P - a by doing an elliptic curve check on the proof com(Q) and the polynomial commitment com(P): we check e(com(Q), com(X - z)) ?= e(com(P) - com(a), com(1)) Some key properties that are important to understand are:A proof is just the com(Q) value, which is 48 bytes com(P₁) + com(P₂) = com(P₁ + P₂) This also means that you can "edit" a value into an existing a commitment. Suppose that we know that D_i is currently a, we want to set it to b, and the existing commitment to D is com(P). A commitment to "P, but with P(wⁱ) = b, and no other evaluations changed", then we set com(new_P) = com(P) + (b-a) * com(Lᵢ), where Lᵢ is a the "Lagrange polynomial" that equals 1 at wⁱ and 0 at other wʲ points. To perform these updates efficiently, all N commitments to Lagrange polynomials (com(Lᵢ)) can be pre-calculated and stored by each client. Inside a contract on-chain it may be too much to store all N commitments, so instead you could make a KZG commitment to the set of com(L_i) (or hash(com(L_i)) values, so whenever someone needs to update the tree on-chain they can simply provide the appropriate com(L_i) with a proof of its correctness. Hence, we have a structure where we can just keep adding values to the end of an ever-growing list, though with a certain size limit (realistically, hundreds of millions could be viable). We then use that as our data structure to manage (i) a commitment to the list of keys on each L2, stored on that L2 and mirrored to L1, and (ii) a commitment to the list of L2 key-commitments, stored on the Ethereum L1 and mirrored to each L2.Keeping the commitments updated could either become part of core L2 logic, or it could be implemented without L2 core-protocol changes through deposit and withdraw bridges. A full proof would thus require:The latest com(key list) on the keystore-holding L2 (48 bytes) KZG proof of com(key list) being a value inside com(mirror_list), the commitment to the list of all key list comitments (48 bytes) KZG proof of your key in com(key list) (48 bytes, plus 4 bytes for the index) It's actually possible to merge the two KZG proofs into one, so we get a total size of only 100 bytes.Note one subtlety: because the key list is a list, and not a key/value map like the state is, the key list will have to assign positions sequentially. The key commitment contract would contain its own internal registry mapping each keystore to an ID, and for each key it would store hash(key, address of the keystore) instead of just key, to unambiguously communicate to other L2s which keystore a particular entry is talking about.The upside of this technique is that it performs very well on L2. The data is 100 bytes, ~4x shorter than a ZK-SNARK and waaaay shorter than a Merkle proof. The computation cost is largely one size-2 pairing check, or about 119,000 gas. On L1, data is less important than computation, and so unfortunately KZG is somewhat more expensive than Merkle proofs.How would Verkle trees work?Verkle trees essentially involve stacking KZG commitments (or IPA commitments, which can be more efficient and use simpler cryptography) on top of each other: to store 2⁴⁸ values, you can make a KZG commitment to a list of 2²⁴ values, each of which itself is a KZG commitment to 2²⁴ values. Verkle trees are being strongly considered for the Ethereum state tree, because Verkle trees can be used to hold key-value maps and not just lists (basically, you can make a size-2²⁵⁶ tree but start it empty, only filling in specific parts of the tree once you actually need to fill them). What a Verkle tree looks like. In practice, you might give each node a width of 256 == 2⁸ for IPA-based trees, or 2²⁴ for KZG-based trees. Proofs in Verkle trees are somewhat longer than KZG; they might be a few hundred bytes long. They are also difficult to verify, especially if you try to aggregate many proofs into one.Realistically, Verkle trees should be considered to be like Merkle trees, but more viable without SNARKing (because of the lower data costs), and cheaper with SNARKing (because of lower prover costs).The largest advantage of Verkle trees is the possibility of harmonizing data structures: Verkle proofs could be used directly over L1 or L2 state, without overlay structures, and using the exact same mechanism for L1 and L2. Once quantum computers become an issue, or once proving Merkle branches becomes efficient enough, Verkle trees could be replaced in-place with a binary hash tree with a suitable SNARK-friendly hash function.AggregationIf N users make N transactions (or more realistically, N ERC-4337 UserOperations) that need to prove N cross-chain claims, we can save a lot of gas by aggregating those proofs: the builder that would be combining those transactions into a block or bundle that goes into a block can create a single proof that proves all of those claims simultaneously.This could mean:A ZK-SNARK proof of N Merkle branches A KZG multi-proof A Verkle multi-proof (or a ZK-SNARK of a multi-proof) In all three cases, the proofs would only cost a few hundred thousand gas each. The builder would need to make one of these on each L2 for the users in that L2; hence, for this to be useful to build, the scheme as a whole needs to have enough usage that there are very often at least a few transactions within the same block on multiple major L2s.If ZK-SNARKs are used, the main marginal cost is simply "business logic" of passing numbers around between contracts, so perhaps a few thousand L2 gas per user. If KZG multi-proofs are used, the prover would need to add 48 gas for each keystore-holding L2 that is used within that block, so the marginal cost of the scheme per user would add another ~800 L1 gas per L2 (not per user) on top. But these costs are much lower than the costs of not aggregating, which inevitably involve over 10,000 L1 gas and hundreds of thousands of L2 gas per user. For Verkle trees, you can either use Verkle multi-proofs directly, adding around 100-200 bytes per user, or you can make a ZK-SNARK of a Verkle multi-proof, which has similar costs to ZK-SNARKs of Merkle branches but is significantly cheaper to prove.From an implementation perspective, it's probably best to have bundlers aggregate cross-chain proofs through the ERC-4337 account abstraction standard. ERC-4337 already has a mechanism for builders to aggregate parts of UserOperations in custom ways. There is even an implementation of this for BLS signature aggregation, which could reduce gas costs on L2 by 1.5x to 3x depending on what other forms of compression are included. Diagram from a BLS wallet implementation post showing the workflow of BLS aggregate signatures within an earlier version of ERC-4337. The workflow of aggregating cross-chain proofs will likely look very similar.Direct state readingA final possibility, and one only usable for L2 reading L1 (and not L1 reading L2), is to modify L2s to let them make static calls to contracts on L1 directly.This could be done with an opcode or a precompile, which allows calls into L1 where you provide the destination address, gas and calldata, and it returns the output, though because these calls are static-calls they cannot actually change any L1 state. L2s have to be aware of L1 already to process deposits, so there is nothing fundamental stopping such a thing from being implemented; it is mainly a technical implementation challenge (see: this RFP from Optimism to support static calls into L1).Notice that if the keystore is on L1, and L2s integrate L1 static-call functionality, then no proofs are required at all! However, if L2s don't integrate L1 static-calls, or if the keystore is on L2 (which it may eventually have to be, once L1 gets too expensive for users to use even a little bit), then proofs will be required.How does L2 learn the recent Ethereum state root?All of the schemes above require the L2 to access either the recent L1 state root, or the entire recent L1 state. Fortunately, all L2s have some functionality to access the recent L1 state already. This is because they need such a functionality to process messages coming in from L1 to the L2, most notably deposits.And indeed, if an L2 has a deposit feature, then you can use that L2 as-is to move L1 state roots into a contract on the L2: simply have a contract on L1 call the BLOCKHASH opcode, and pass it to L2 as a deposit message. The full block header can be received, and its state root extracted, on the L2 side. However, it would be much better for every L2 to have an explicit way to access either the full recent L1 state, or recent L1 state roots, directly.The main challenge with optimizing how L2s receive recent L1 state roots is simultaneously achieving safety and low latency:If L2s implement "direct reading of L1" functionality in a lazy way, only reading finalized L1 state roots, then the delay will normally be 15 minutes, but in the extreme case of inactivity leaks (which you have to tolerate), the delay could be several weeks. L2s absolutely can be designed to read much more recent L1 state roots, but because L1 can revert (even with single slot finality, reverts can happen during inactivity leaks), L2 would need to be able to revert as well. This is technically challenging from a software engineering perspective, but at least Optimism already has this capability. If you use the deposit bridge to bring L1 state roots into L2, then simple economic viability might require a long time between deposit updates: if the full cost of a deposit is 100,000 gas, and we assume ETH is at $1800, and fees are at 200 gwei, and L1 roots are brought into L2 once per day, that would be a cost of $36 per L2 per day, or $13148 per L2 per year to maintain the system. With a delay of one hour, that goes up to $315,569 per L2 per year. In the best case, a constant trickle of impatient wealthy users covers the updating fees and keep the system up to date for everyone else. In the worst case, some altruistic actor would have to pay for it themselves. "Oracles" (at least, the kind of tech that some defi people call "oracles") are not an acceptable solution here: wallet key management is a very security-critical low-level functionality, and so it should depend on at most a few pieces of very simple, cryptographically trustless low-level infrastructure. Additionally, in the opposite direction (L1s reading L2):On optimistic rollups, state roots take one week to reach L1 because of the fraud proof delay. On ZK rollups it takes a few hours for now because of a combination of proving times and economic limits, though future technology will reduce this. Pre-confirmations (from sequencers, attesters, etc) are not an acceptable solution for L1 reading L2. Wallet management is a very security-critical low-level functionality, and so the level of security of the L2 -> L1 communication must be absolute: it should not even be possible to push a false L1 state root by taking over the L2 validator set. The only state roots the L1 should trust are state roots that have been accepted as final by the L2's state-root-holding contract on L1. Some of these speeds for trustless cross-chain operations are unacceptably slow for many defi use cases; for those cases, you do need faster bridges with more imperfect security models. For the use case of updating wallet keys, however, longer delays are more acceptable: you're not delaying transactions by hours, you're delaying key changes. You'll just have to keep the old keys around longer. If you're changing keys because keys are stolen, then you do have a significant period of vulnerability, but this can be mitigated, eg. by wallets having a freeze function.Ultimately, the best latency-minimizing solution is for L2s to implement direct reading of L1 state roots in an optimal way, where each L2 block (or the state root computation log) contains a pointer to the most recent L1 block, so if L1 reverts, L2 can revert as well. Keystore contracts should be placed either on mainnet, or on L2s that are ZK-rollups and so can quickly commit to L1. Blocks of the L2 chain can have dependencies on not just previous L2 blocks, but also on an L1 block. If L1 reverts past such a link, the L2 reverts too. It's worth noting that this is also how an earlier (pre-Dank) version of sharding was envisioned to work; see here for code. How much connection to Ethereum does another chain need to hold wallets whose keystores are rooted on Ethereum or an L2?Surprisingly, not that much. It actually does not even need to be a rollup: if it's an L3, or a validium, then it's okay to hold wallets there, as long as you hold keystores either on L1 or on a ZK rollup. The thing that you do need is for the chain to have direct access to Ethereum state roots, and a technical and social commitment to be willing to reorg if Ethereum reorgs, and hard fork if Ethereum hard forks.One interesting research problem is identifying to what extent it is possible for a chain to have this form of connection to multiple other chains (eg. Ethereum and Zcash). Doing it naively is possible: your chain could agree to reorg if Ethereum or Zcash reorg (and hard fork if Ethereum or Zcash hard fork), but then your node operators and your community more generally have double the technical and political dependencies. Hence such a technique could be used to connect to a few other chains, but at increasing cost. Schemes based on ZK bridges have attractive technical properties, but they have the key weakness that they are not robust to 51% attacks or hard forks. There may be more clever solutions.Preserving privacyIdeally, we also want to preserve privacy. If you have many wallets that are managed by the same keystore, then we want to make sure:It's not publicly known that those wallets are all connected to each other. Social recovery guardians don't learn what the addresses are that they are guarding. This creates a few issues:We cannot use Merkle proofs directly, because they do not preserve privacy. If we use KZG or SNARKs, then the proof needs to provide a blinded version of the verification key, without revealing the location of the verification key. If we use aggregation, then the aggregator should not learn the location in plaintext; rather, the aggregator should receive blinded proofs, and have a way to aggregate those. We can't use the "light version" (use cross-chain proofs only to update keys), because it creates a privacy leak: if many wallets get updated at the same time due to an update procedure, the timing leaks the information that those wallets are likely related. So we have to use the "heavy version" (cross-chain proofs for each transaction). With SNARKs, the solutions are conceptually easy: proofs are information-hiding by default, and the aggregator needs to produce a recursive SNARK to prove the SNARKs. The main challenge of this approach today is that aggregation requires the aggregator to create a recursive SNARK, which is currently quite slow.With KZG, we can use this work on non-index-revealing KZG proofs (see also: a more formalized version of that work in the Caulk paper) as a starting point. Aggregation of blinded proofs, however, is an open problem that requires more attention.Directly reading L1 from inside L2, unfortunately, does not preserve privacy, though implementing direct-reading functionality is still very useful, both to minimize latency and because of its utility for other applications.SummaryTo have cross-chain social recovery wallets, the most realistic workflow is a wallet that maintains a keystore in one location, and wallets in many locations, where wallet reads the keystore either (i) to update their local view of the verification key, or (ii) during the process of verifying each transaction. A key ingredient of making this possible is cross-chain proofs. We need to optimize these proofs hard. Either ZK-SNARKs, waiting for Verkle proofs, or a custom-built KZG solution, seem like the best options. In the longer term, aggregation protocols where bundlers generate aggregate proofs as part of creating a bundle of all the UserOperations that have been submitted by users will be necessary to minimize costs. This should probably be integrated into the ERC-4337 ecosystem, though changes to ERC-4337 will likely be required. L2s should be optimized to minimize the latency of reading L1 state (or at least the state root) from inside the L2. L2s directly reading L1 state is ideal and can save on proof space. Wallets can be not just on L2s; you can also put wallets on systems with lower levels of connection to Ethereum (L3s, or even separate chains that only agree to include Ethereum state roots and reorg or hard fork when Ethereum reorgs or hardforks). However, keystores should be either on L1 or on high-security ZK-rollup L2 . Being on L1 saves a lot of complexity, though in the long run even that may be too expensive, hence the need for keystores on L2. Preserving privacy will require additional work and make some options more difficult. However, we should probably move toward privacy-preserving solutions anyway, and at the least make sure that anything we propose is forward-compatible with preserving privacy. -

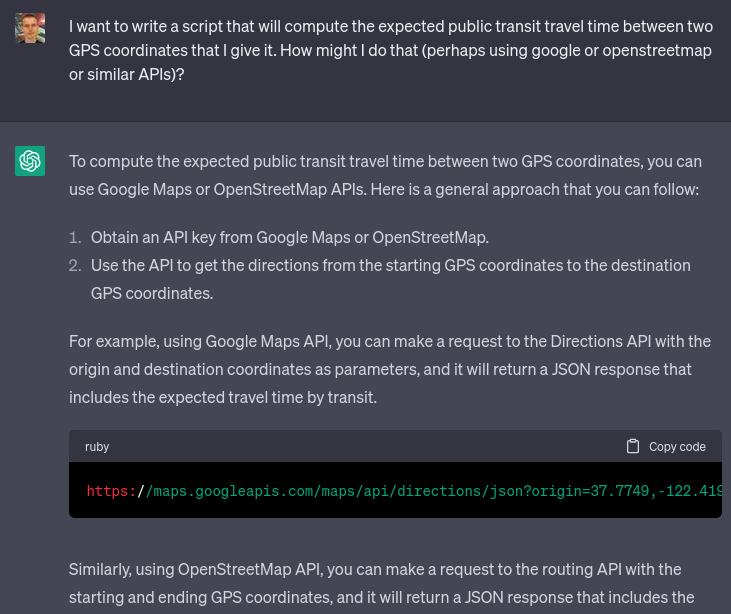

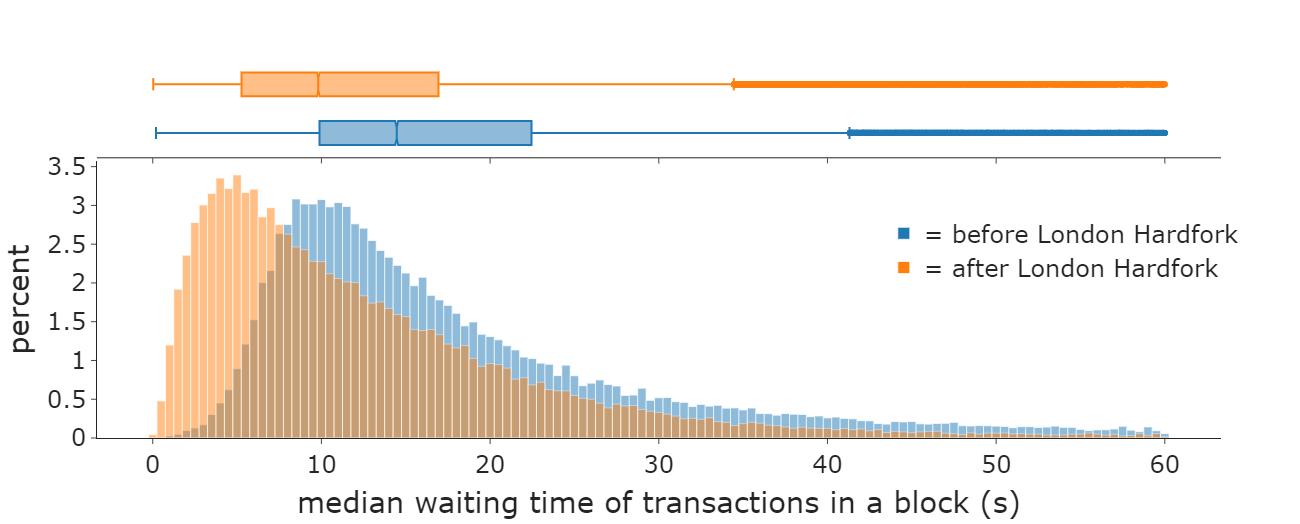

Travel time ~= 750 * distance ^ 0.6 Travel time ~= 750 * distance ^ 0.62023 Apr 14 See all posts Travel time ~= 750 * distance ^ 0.6 As another exercise in using ChatGPT 3.5 to do weird things and seeing what happens, I decided to explore an interesting question: how does the time it takes to travel from point A to point B scale with distance, in the real world? That is to say, if you sample randomly from positions where people are actually at (so, for example, 56% of points you choose would be in cities), and you use public transportation, how does travel time scale with distance?Obviously, travel time would grow slower than linearly: the further you have to go, the more opportunity you have to resort to forms of transportation that are faster, but have some fixed overhead. Outside of a very few lucky cases, there is no practical way to take a bus to go faster if your destination is 170 meters away, but if your destination is 170 kilometers away, you suddenly get more options. And if it's 1700 kilometers away, you get airplanes.So I asked ChatGPT for the ingredients I would need: I went with the GeoLife dataset. I did notice that while it claims to be about users around the world, primarily it seems to focus on people in Seattle and Beijing, though they do occasionally visit other cities. That said, I'm not a perfectionist and I was fine with it. I asked ChatGPT to write me a script to interpret the dataset and extract a randomly selected coordinate from each file: Amazingly, it almost succeeded on the first try. It did make the mistake of assuming every item in the list would be a number (values = [float(x) for x in line.strip().split(',')]), though perhaps to some extent that was my fault: when I said "the first two values" it probably interpreted that as implying that the entire line was made up of "values" (ie. numbers).I fixed the bug manually. Now, I have a way to get some randomly selected points where people are at, and I have an API to get the public transit travel time between the points.I asked it for more coding help:Asking how to get an API key for the Google Maps Directions API (it gave an answer that seems to be outdated, but that succeeded at immediately pointing me to the right place) Writing a function to compute the straight-line distance between two GPS coordinates (it gave the correct answer on the first try) Given a list of (distance, time) pairs, drawing a scatter plot, with time and distance as axes, both axes logarithmically scaled (it gave the correct answer on the first try) Doing a linear regression on the logarithms of distance and time to try to fit the data to a power law (it bugged on the first try, succeeded on the second) This gave me some really nice data (this is filtered for distances under 500km, as above 500km the best path almost certainly includes flying, and the Google Maps directions don't take into account flights): The power law fit that the linear regression gave is: travel_time = 965.8020738916074 * distance^0.6138556361612214 (time in seconds, distance in km).Now, I needed travel time data for longer distances, where the optimal route would include flights. Here, APIs could not help me: I asked ChatGPT if there were APIs that could do such a thing, and it did not give a satisfactory answer. I resorted to doing it manually:I used the same script, but modified it slightly to only output pairs of points which were more than 500km apart from each other. I took the first 8 results within the United States, and the first 8 with at least one end outside the United States, skipping over results that represented a city pair that had already been covered. For each result I manually obtained: to_airport: the public transit travel time from the starting point to the nearest airport, using Google Maps outside China and Baidu Maps inside China. from_airport: the public transit travel time to the end point from the nearest airport flight_time: the flight time from the starting point to the end point. I used Google Flights) and always took the top result, except in cases where the top result was completely crazy (more than 2x the length of the shortest), in which case I took the shortest. I computed the travel time as (to_airport) * 1.5 + (90 if international else 60) + flight_time + from_airport. The first part is a fairly aggressive formula (I personally am much more conservative than this) for when to leave for the airport: aim to arrive 60 min before if domestic and 90 min before if international, and multiply expected travel time by 1.5x in case there are any mishaps or delays. This was boring and I was not interested in wasting my time to do more than 16 of these; I presume if I was a serious researcher I would already have an account set up on TaskRabbit or some similar service that would make it easier to hire other people to do this for me and get much more data. In any case, 16 is enough; I put my resulting data here.Finally, just for fun, I added some data for how long it would take to travel to various locations in space: the moon (I added 12 hours to the time to take into account an average person's travel time to the launch site), Mars, Pluto and Alpha Centauri. You can find my complete code here.Here's the resulting chart: travel_time = 733.002223593754 * distance^0.591980777827876 WAAAAAT?!?!! From this chart it seems like there is a surprisingly precise relationship governing travel time from point A to point B that somehow holds across such radically different transit media as walking, subways and buses, airplanes and (!!) interplanetary and hypothetical interstellar spacecraft. I swear that I am not cherrypicking; I did not throw out any data that was inconvenient, everything (including the space stuff) that I checked I put on the chart.ChatGPT 3.5 worked impressively well this time; it certainly stumbled and fell much less than my previous misadventure, where I tried to get it to help me convert IPFS bafyhashes into hex. In general, ChatGPT seems uniquely good at teaching me about libraries and APIs I've never heard of before but that other people use all the time; this reduces the barrier to entry between amateurs and professionals which seems like a very positive thing.So there we go, there seems to be some kind of really weird fractal law of travel time. Of course, different transit technologies could change this relationship: if you replace public transit with cars and commercial flights with private jets, travel time becomes somewhat more linear. And once we upload our minds onto computer hardware, we'll be able to travel to Alpha Centauri on much crazier vehicles like ultralight craft propelled by Earth-based lightsails) that could let us go anywhere at a significant fraction of the speed of light. But for now, it does seem like there is a strangely consistent relationship that puts time much closer to the square root of distance.

Travel time ~= 750 * distance ^ 0.6 Travel time ~= 750 * distance ^ 0.62023 Apr 14 See all posts Travel time ~= 750 * distance ^ 0.6 As another exercise in using ChatGPT 3.5 to do weird things and seeing what happens, I decided to explore an interesting question: how does the time it takes to travel from point A to point B scale with distance, in the real world? That is to say, if you sample randomly from positions where people are actually at (so, for example, 56% of points you choose would be in cities), and you use public transportation, how does travel time scale with distance?Obviously, travel time would grow slower than linearly: the further you have to go, the more opportunity you have to resort to forms of transportation that are faster, but have some fixed overhead. Outside of a very few lucky cases, there is no practical way to take a bus to go faster if your destination is 170 meters away, but if your destination is 170 kilometers away, you suddenly get more options. And if it's 1700 kilometers away, you get airplanes.So I asked ChatGPT for the ingredients I would need: I went with the GeoLife dataset. I did notice that while it claims to be about users around the world, primarily it seems to focus on people in Seattle and Beijing, though they do occasionally visit other cities. That said, I'm not a perfectionist and I was fine with it. I asked ChatGPT to write me a script to interpret the dataset and extract a randomly selected coordinate from each file: Amazingly, it almost succeeded on the first try. It did make the mistake of assuming every item in the list would be a number (values = [float(x) for x in line.strip().split(',')]), though perhaps to some extent that was my fault: when I said "the first two values" it probably interpreted that as implying that the entire line was made up of "values" (ie. numbers).I fixed the bug manually. Now, I have a way to get some randomly selected points where people are at, and I have an API to get the public transit travel time between the points.I asked it for more coding help:Asking how to get an API key for the Google Maps Directions API (it gave an answer that seems to be outdated, but that succeeded at immediately pointing me to the right place) Writing a function to compute the straight-line distance between two GPS coordinates (it gave the correct answer on the first try) Given a list of (distance, time) pairs, drawing a scatter plot, with time and distance as axes, both axes logarithmically scaled (it gave the correct answer on the first try) Doing a linear regression on the logarithms of distance and time to try to fit the data to a power law (it bugged on the first try, succeeded on the second) This gave me some really nice data (this is filtered for distances under 500km, as above 500km the best path almost certainly includes flying, and the Google Maps directions don't take into account flights): The power law fit that the linear regression gave is: travel_time = 965.8020738916074 * distance^0.6138556361612214 (time in seconds, distance in km).Now, I needed travel time data for longer distances, where the optimal route would include flights. Here, APIs could not help me: I asked ChatGPT if there were APIs that could do such a thing, and it did not give a satisfactory answer. I resorted to doing it manually:I used the same script, but modified it slightly to only output pairs of points which were more than 500km apart from each other. I took the first 8 results within the United States, and the first 8 with at least one end outside the United States, skipping over results that represented a city pair that had already been covered. For each result I manually obtained: to_airport: the public transit travel time from the starting point to the nearest airport, using Google Maps outside China and Baidu Maps inside China. from_airport: the public transit travel time to the end point from the nearest airport flight_time: the flight time from the starting point to the end point. I used Google Flights) and always took the top result, except in cases where the top result was completely crazy (more than 2x the length of the shortest), in which case I took the shortest. I computed the travel time as (to_airport) * 1.5 + (90 if international else 60) + flight_time + from_airport. The first part is a fairly aggressive formula (I personally am much more conservative than this) for when to leave for the airport: aim to arrive 60 min before if domestic and 90 min before if international, and multiply expected travel time by 1.5x in case there are any mishaps or delays. This was boring and I was not interested in wasting my time to do more than 16 of these; I presume if I was a serious researcher I would already have an account set up on TaskRabbit or some similar service that would make it easier to hire other people to do this for me and get much more data. In any case, 16 is enough; I put my resulting data here.Finally, just for fun, I added some data for how long it would take to travel to various locations in space: the moon (I added 12 hours to the time to take into account an average person's travel time to the launch site), Mars, Pluto and Alpha Centauri. You can find my complete code here.Here's the resulting chart: travel_time = 733.002223593754 * distance^0.591980777827876 WAAAAAT?!?!! From this chart it seems like there is a surprisingly precise relationship governing travel time from point A to point B that somehow holds across such radically different transit media as walking, subways and buses, airplanes and (!!) interplanetary and hypothetical interstellar spacecraft. I swear that I am not cherrypicking; I did not throw out any data that was inconvenient, everything (including the space stuff) that I checked I put on the chart.ChatGPT 3.5 worked impressively well this time; it certainly stumbled and fell much less than my previous misadventure, where I tried to get it to help me convert IPFS bafyhashes into hex. In general, ChatGPT seems uniquely good at teaching me about libraries and APIs I've never heard of before but that other people use all the time; this reduces the barrier to entry between amateurs and professionals which seems like a very positive thing.So there we go, there seems to be some kind of really weird fractal law of travel time. Of course, different transit technologies could change this relationship: if you replace public transit with cars and commercial flights with private jets, travel time becomes somewhat more linear. And once we upload our minds onto computer hardware, we'll be able to travel to Alpha Centauri on much crazier vehicles like ultralight craft propelled by Earth-based lightsails) that could let us go anywhere at a significant fraction of the speed of light. But for now, it does seem like there is a strangely consistent relationship that puts time much closer to the square root of distance. -